One of the best things about working for a high-end bike rental platform is getting to test out the bikes we offer. Roula Community Lead Amelia Rina caught up with Ben Serotta and talked to him about his new company, Serotta Design Studios, and what went into the most recent addition to his legacy of highly considerate bikes: the Duetti.

—–

Amelia Rina: How did you first get into cycling?

Ben Serotta: What brought me to making bikes was an overlapping love of riding, exploring, and making things. My mother is Dutch and grew up in Holland, which has been known as the land of bicycles for decades. My mom used to tell me all these wonderful stories when I was a child about adventures that she and her siblings and friends would take on bikes. So with her influence, I really enjoyed riding a bike from a young age.

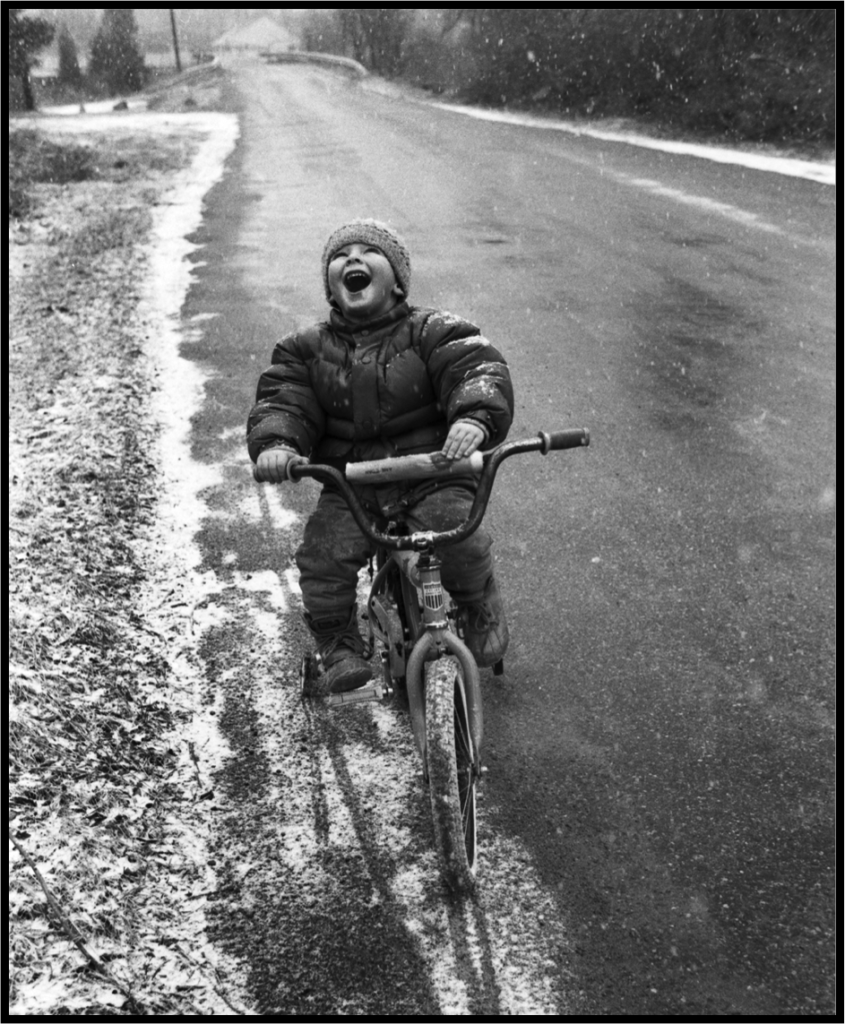

My favorite cycling picture is of a 3-year old boy riding a bike in a snowstorm with an expression of just pure exhilaration and joy. For me, the picture shows that riding a bike is freedom. That sensation captured in the photo has really never left me.

In addition to loving cycling, my mom’s siblings, parents, and their parents are all artisans of one type or another. I grew up in a household in which making anything was never too complicated or daunting—if you wanted to make something, you just figure it out and do it. Building bikes was a natural progression for me because I liked riding bikes and making things. Of course, my early bikes were nothing special. I started taking bikes apart and combining parts, then I kept tinkering, adjusting, and experimenting.

For me, bikes are functional art. I enjoy looking at very high quality things, but I find greater satisfaction when things are also functional. I prioritize function over form, or, more accurately, function always drives form. As a life-long entrepreneur, I have had to be a business person too, which in itself can be gratifying, satisfying, even exhilarating, but it just doesn’t provide the same kind of satisfaction to me as making something so physically interactive as the process that goes into making a bike.

AR: Let’s talk about the Duetti, which, as I mentioned when we were corresponding earlier, I’ve been riding for a few weeks. I live in Bushwick and commute to the Roula office, which is about 9 miles each away.

BS: 9 miles of death-defying physics, I bet.

AR: Yeah, it’s basically New York’s urban cyclocross course. There were a few times riding I wanted to sort of stress-test the Duetti to see how it performed, so I rode over some of the questionably-paved roads that I would normally avoid, and the bike performed beautifully. It was so smooth. What went into the design and the materials used for the Duetti?

BS: The goal was to offer a bicycle that was simple to understand in terms of why you wanted it. I spent the better part of the last 40 years in my previous company offering more and more options. That was largely because 95 percent of our business was to bicycle retailers, and not to insult anyone, but most people in sales simply want to offer whatever anybody might possibly be looking for. If you let yourself develop your product based on what salespeople want, you can end up with a seriously extensive—and, to a degree meaningless—product range, and the brand loses its message (unless of course the brand message is that we just make anything you ask for). To me, that makes a weak case for why a brand should be in business. I’d like to believe that with focus and clarity of vision and design, it’s possible to offer products that are distinctly better.

I realized that most of the customers or potential customers I spoke with wanted to know what I thought would be the best bike for them. So, starting with a road bike, I wanted to develop a bicycle for someone who might say “I’m a road cyclist and I want one bike that does everything really well.” That’s the ultimate goal of the Duetti—not to have 15 different versions of something that are so close that even the language is the same across a range of models. That’s just confusing.

AR: What do you think is the most important element of choosing the right bike?

BS: The most important thing behind any bike is getting the fit right, so the cyclist can fit the bike well, and the bike underneath the cyclist is proportioned well. Those sound like the same thing, but they’re actually not. You can have a bike that has a frame and fork made in three sizes, and by changing stems, handlebars, and seat posts, you can kind of fit almost everyone onto one of those three frame sizes. That doesn’t mean that the bike is going to ride equally well for all those people, because of differences in weight distribution and so forth.

I wanted to create a bike that uses the experience I gained through the tens of thousands of custom bikes I’ve built, and create size parameters based on those bikes to predict what are most likely the geometry configurations that will work for a very large audience. That came down to an initial 9 sizes, and we’ve added in a couple extra-large and smaller bikes built with a smaller wheel size, which allows us to build a bike that the cyclist can sit on with proper fit and balance.

To be able to do that really led me towards making a bike in metal, as opposed to carbon fiber. I’m not saying that I’m anti-carbon fiber, it’s just that to make a great carbon fiber bike in many sizes is a hugely expensive undertaking, which is why most companies kind of fake their size ranges. Besides, carbon composite is just another material, and like other materials, it can be turned into great product or mediocre product. In tests, I felt that our alloy was the equal or better in road feel than any of the ‘black plastic’ bikes I’ve tried.

AR: Is that what made you decide to make the Duetti in this particular aluminum alloy?

BS: I wanted to build a bike that allowed for the range of geometries I developed, and then the next requirement was great performance and longevity. I had some experience with aluminum in the past, but I would say that like most aluminum bikes, the ride was not inspiring. Typically they were and are just darn stiff, so that they don’t fail. That’s what brought me to this alloy with vanadium.

AR: I did some research on vanadium, it seems like a fascinating material.

BS: It is, and there’s only a small percentage of vanadium in any alloy that uses it. This particular alloy—6069 with vanadium—and the post-welding process called shot peening produce a critical transformation in the aluminum, which is typically a material that is light and stiff, but not particularly durable. In the past you could either have a bike that’s light and super stiff and therefore have some durability, or you can make it light and somewhat lively feeling but then doesn’t have a long shelf life, so to speak. The key was finding the alloy that had vanadium in it. Higher quality steels, such as the Colombus tubing I use in my steel bikes, have vanadium in them, as do most titanium alloys. When it’s used in any metal alloy combination, it adds durability.

AR: What does the shot peening process add to the material?

BS: An interesting thing about shot peening, which is not a complicated process, is that it’s pretty much not used in the bike industry with the exception of a couple companies that are doing things with similar alloys and trying to achieve a durable, lightweight product. Like many manufacturing technologies, its first use was in military applications where critical components needed to be able to endure high stress and cyclical vibration yet not be too heavy. Propellers (both naval and aeronautical) are an example. The shot peening alone can improve the material life cycle by more than 300% and then in combination with the 6069 alloy, we can do the kind of tube engineering that really pumps up the character of the ride of the bike: stiff where it needs to be, smooth where is doesn’t need to be stiff.

In all the bikes I’ve done over the years, my goal has been to try to deliver a ride that really makes great use of your energy by making the bike very efficient, while maintaining a level of compliance and vibration damping so that you’re not getting beat up over the course of a ride. The benefit of vibration damping and compliance is that it actually saves energy. When you’re subject to impact, your muscles involuntarily try to offset whatever stress is affecting them. You burn up a lot of energy just trying to resist the vibration, so having a bike that’s purely stiff doesn’t do you any favors. The goal with the Duetti was to build a bike that moves with you. The name Duetti, which is Italian for “duets,” came from this concept of a cyclist and the bike working with each other. A stiff bike can feel fast and extremely responsive, but it is also working against you in ways other than just the vibration; it puts added stress on your skeleton and joints and its harder to grip and hold a line in hard cornering. Ideally, a bike (the wheels, frame and fork, cranks) has a bit of give vertically, laterally, and torsionally, so the bike actually works with you when you’re climbing, sprinting out of the saddle, or when you’re cornering. That was the design concept behind the Duetti. To achieve these things—fit, proportion, feel—that were effectively only available in titanium or steel, in a bike that is also a little bit lighter and affordable.

AR: The properties of vanadium align nicely with how you describe your goals for the Duetti. I read that vanadium batteries are very stable and efficient because electrons can easily be removed or added from the metal, which allows the batteries to be discharged and recharged 20,000 times with little loss in performance. So the alloy acts as a kind of extension of what the bike does: it facilitates a flow of energy between the rider and the machine, allowing them to work together more efficiently and almost recharging because you don’t have the vibrations fatigue that you might get from a stiffer bike.

BS: I love that! I hadn’t considered how vanadium is used in batteries, but it does work as a great metaphor.

AR: I also read that element was named after the Norse goddess of beauty, Vanadis! It’s such an interesting material.

BS: It really is a miraculous thing that largely has been overlooked. The Duetti also takes into consideration that there’s no such thing as a bike that does 10 different things equally well. For example, there’s been a lot of buzz over the last several years for gravel bikes by a variety of different names, and there are quite a few bikes built today that can accept many different sizes of wheels and so forth. What I wanted to do for a first bike was try to consider what, honestly, most road cyclists are going to be using the bike for. It’s optimized for the majority of riding road cyclists will do, yet it’s still more than capable of handling other stuff.

I grew up making race bikes and they had really skinny little tires, but because of where I live in Upstate New York, I rarely go on a ride that doesn’t include a little bit of the dirt road or something being repaved or whatever. With 25mm or 28mm tires, the Duetti is plenty buoyant for riding on a lot rougher or somewhat looser surfaces. The disc brake version will also fit some 32mm road tires.

AR: Since launching Serotta Design Studios in January of this year you’ve released the Duetti and a fully-custom steel model called aModoMio (Italian for “my way”). What do you have planned for the future?

BS: Toward the end of this year we’ll have another model. In the same way that the Duetti assumes that most of your riding will be on paved or packed surfaces, the next model will assume that the sweet spot of your joy time is spent on something that is less manicured.

AR: That’s exciting! Although, I took that Duetti onto some grass, some hard pack dirt, and through some big puddles with very questionable bottoms, and it was great.

BS: You know, we’re a culture that likes equipment. I don’t fish, but when I was growing up my family had a hardware store where I hung out all time. One of the fellas there, Tommy, was a legendary fisherman in the area. He always caught fish, and he pretty much used the simplest rod and the shittiest old pair of wader boots. Then I’d see all these city folk coming upstate, completely geared out in brand new stuff from LL Bean or something like that, and rods that cost ten times whatever Tommy’s did, and they either didn’t catch anything, or certainly didn’t catch more than he did. But having the gear was clearly part of the enjoyment, and we can’t deny that’s still a reality today.

I’m not at all saying that there is anything wrong with being fully decked out in the latest gear. I like all the cool stuff too! It’s just not our sales focus in the way it is with many of the high-end retailers. Rather, at Serotta Design Studio, simply put, the goal is to help my customers discover the bike that they will love to ride, and ride, and ride.